The Death of Documentary and why are people tuning out of TV

Content warning: This piece includes a brief discussion of suicide and mental illness.

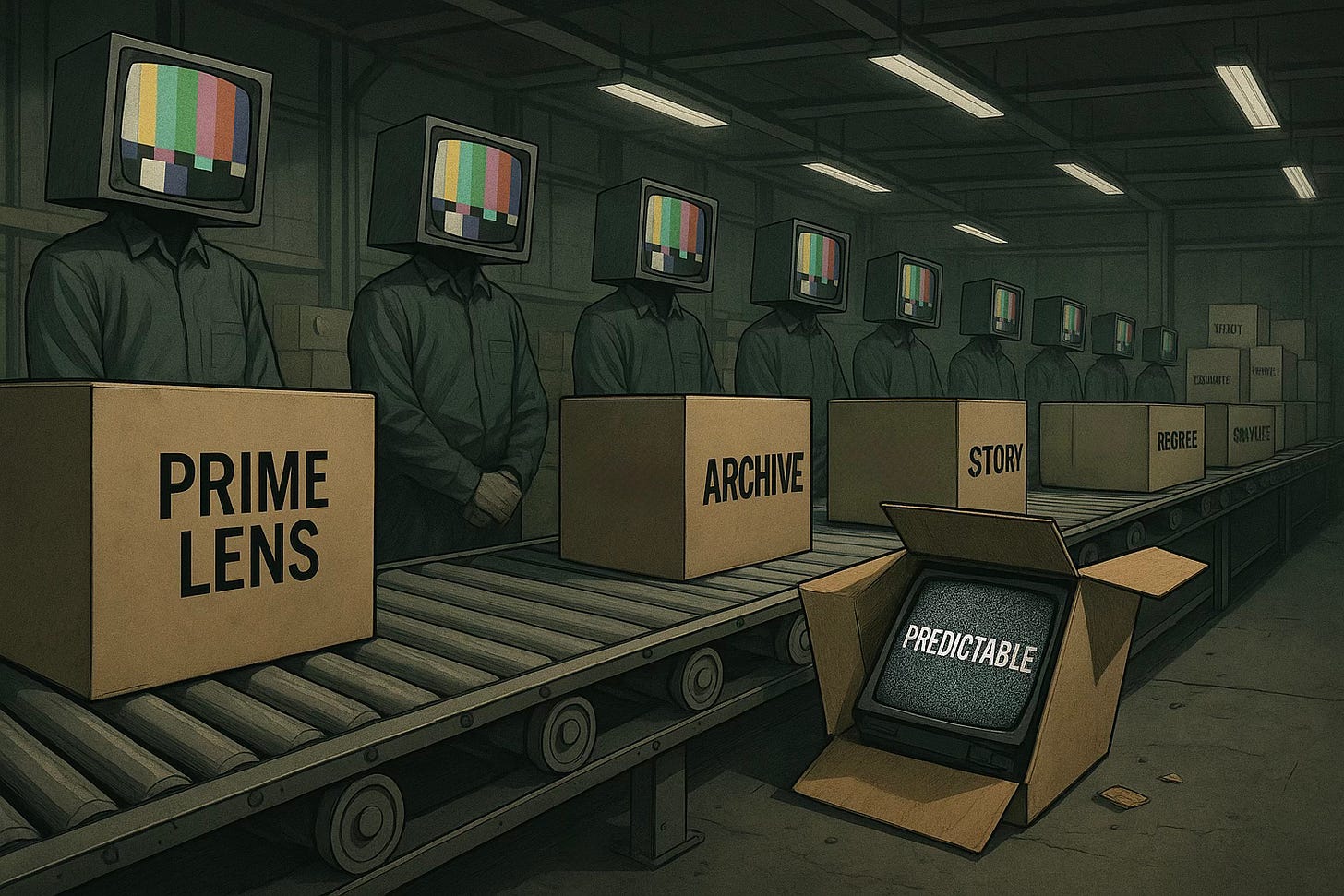

People aren't just deserting linear TV because it's more convenient to watch long-form TV whenever they want on digital. They're leaving because traditional TV, especially factual, is becoming eminently missable. Not because the stories aren’t important but because the way we’re telling them is putting people off - it’s like as an industry we’ve worked out a successful formula so now we’re churning documentaries out that feel like they’ve popped out of a factory.

What used to be a place for raw, reactive storytelling has been templated into safe, respectable, interview-heavy wallpaper. It’s watchable, but not memorable. Serious, but not surprising and for younger audiences raised on YouTube chaos, TikTok confessionals, and streamers who don’t care about the BAFTAs, it’s just not cutting through.

Which brings me to a bigger fear: this inadvertent repetitiveness not only means are viewers losing interest but the next generation of filmmakers are losing their training ground. The craft of observational storytelling - the school of standing in a police station or airport until a narrative emerges and then working out how to get a beginning and end out of the ensuing chaos. This vital storytelling practice is vanishing only to be replaced by slick re-creations and second camera angles. Essentially compelling actuality is being ignored in favour of soft-formatting.

Remember the dumbbell?

A while back, I said TV content looked a lot like a dumbbell. On one end: super-cheap, high-volume stuff. On the other: super-expensive, prestige content. And in the middle? Not much.

That’s where I believe traditional TV is heading - premium dramas, landmark docs and flashy formats at one end, and cheap, cheerful, high-turnover shows on the other. It’s actually a great place to be. TV has the financial muscle to play at both ends of the scale and deliver brilliant content in both.

But here’s the problem: some genres are being kicked aside in the rush to simplify and systematise production and nowhere is this more obvious than in factual.

Documentary, or more broadly, ‘non-scripted’, is becoming increasingly formulaic, particularly in the historical and crime spaces, and it's in danger of killing off the industry. The editorial pattern of the average doc goes like this:

Interview experts, victims, and key players in photogenic locations. Light them beautifully. Use prime lenses to blow out the background. Get them to stare down the barrel of the lens whilst talking but don't forget to add a second camera for your cutaways - usually at a slightly odd angle to add a bit of ‘Dutch’ to the process.

Slather on the archive. Let it do the heavy lifting.

Can’t find the archive? No problem - cue the tasteful re-cre (if you’re American) or reenactment (if you’re British).

Don't forget maps or other graphics if you're still struggling to cover up the talking heads.

Rinse and repeat until the hour is up.

So here’s the question: is that still documentary? Ask a director who’s made one of these 'films' and they’ll vehemently argue they are documentaries. Ask them if Clarkson’s Farm is a documentary, however, and they’ll look at you like you’ve just insulted their dog.

And yes, while it’s true that a four-part crime doc about a 1970s serial killer might feel 'important' what’s really happening is we’re making all of our docs look and feel the same. No wonder younger viewers crave the intimacy, immediacy and authentic nature of digital. It feels uncontrived, edgy, like you don’t know what’s going to happen next - weirdly how TV used to feel before it became too slick.

I believe we need to seriously look at how we're delivering our stories and how we're training our next generation of programme makers. We need to start appreciating the art of shows like The Grand Tour, Mortimer & WhiteHouse: Gone Fishing or any other fact-ent shows, because hidden in them are big messages that hit home. Beneath the entertainment are sharp, well-told stories they’re often delivering the same societal messaging our 'serious' docs do, but in a more digestible way.

I’m someone who’s lucky enough to have done both types of factual programme making and I’m here to tell you: observational fact-ent is the much tougher gig. Sadly, however, it’s being killed off - not by the audience, but by the industry - and if we're not careful the result will be we'll continue to haemorrhage even more viewers on short form, digital platforms.

Wonky angles, dusty archive and tasteful recon just can’t beat real actuality.

I think we’ve stopped making documentaries and instead we’ve started producing them. Hear me out - there’s a difference.

I’m starting to find that modern documentaries are boring. Yes, they’re polished. Yes, they’re expensive and yes their stories are often powerful. But it’s not enough and it’s not the stories that are at fault - it’s the way we deliver them. All our premium docs look fantastic but all of that gloss comes at a cost that’s not just financial.

What we’re losing is authenticity. The more stylised the image, the less it feels like real life. The more prime lens depth-of-field and drone swoops we use, the more we signal to the audience that what they’re watching isn’t quite the truth - it’s a stylised construction.

That’s the paradox: we’re spending more money to make things look beautiful, to signal to viewers how they should be feeling in a moment. We’re trying so hard to differentiate ourselves in the competition between YouTube and traditional TV that we’re making our content feel less real in the process.

Documentary used to feel unpredictable. It was messy. Grainy. Sometimes ugly but it pulsed with immediacy. Now, too many documentaries feel like they’ve been designed by committee, colour-graded into submission, and spat out with a melancholy score and pre-approved moral arc.

It’s not just that the format is repetitive - it’s that the emotional rhythm is predictable. You know where it’s going. You know what tone it’ll hit. You know how it’ll end and in a world of infinite content, predictability is death.

That’s not risk. That’s recipe and it's a recipe that clearly doesn't work if no-one is watching TV anymore.

The skill we’ve stopped teaching

Before we go further, let me name-check a film that still haunts me: Dave Nath’s Brian’s Story. Made in 2001, it was an incredibly crafted film made by a director who had literally just finished making the ITV series Airline. It followed a man called Brian, a homeless person who once had a 'normal life' as a journalist, through the brutal trial of trying to rebuild his broken life. Brian was unpredictable, suffered terribly from mental illness issues and often found it hard to properly articulate what was going on around him.

Dave spent over a year filming him, often just following, watching, listening. It wasn’t built in post. It was earned, on the street, being at Brian's side. Dave and the commissioner didn’t know how it was going to end but end it did, in a very tragic way.

The result? One of the most powerful portraits of homelessness ever broadcast. A reminder that society doesn’t just fail people once, it fails them again and again until no one notices they’ve vanished. Tragically, Brian died unexpectedly after falling from a window. He had high levels of alcohol in his bloodstream, and it seemed likely he accidentally fell. Whatever the reason, whether he decided to end his life or it was an accident, it was a shocking and devastating conclusion, not just for the audience, but for Dave himself.

It made for one of the most powerful documentaries ever made, but the only reason that was possible, was because everyone involved didn’t know how it was going to end - but they knew whatever the outcome was, that they would be able to tell an incredibly compelling and emotional story. This is documentary making.

But here’s the thing: Dave, like me, came up through the ranks of Airline and Ramsay’s Boiling Point - not from making sit-down interview shows. We made shows where you had to sink or swim, find a narrative in chaos, and fight for every frame. His later success in documentaries wasn’t a coincidence it was because of those early years spent in the fire. I honestly believe if he hadn’t of made those earlier fact-ent shows, he wouldn't have been able to tell Brain’s story the way he did.

So where does that leave us?

We need to start saying something uncomfortable out loud: a lot of young filmmakers aren’t being trained properly and I don’t mean at film school, I mean out in the field making observation documentaries for broadcast. Not because they lack talent but because that type of show isn’t really being commissioned anymore.

Instead, factual shows now work on tightened timelines, very often a ‘director’ either wont edit what they have shot or vice versa. There’s no room for unpredictable ob-doc and even if there is, no one person goes through the full editorial journey anymore. If you don’t own the full process you wont be able to learn new skills, or learn from making mistakes. If you’ve never had to dig a narrative out of a day of live chaos unfolding right before your eyes, you don’t learn how story actually works.

And this is where the broadcasters need to listen.

We need more risk in the way we tell stories. Yes, it’ll cost you. Yes, it might take longer and it’s not very efficient - but by god you get a better story at the end and isn’t that exactly what HETV has been built on? You’re already spending big on drama, so why are you squeezing your factual slate into 12-month slots and glossy templates?

Stop obsessing over beauty. Start obsessing over truth. Commission documentaries where no one - not even the director - knows how it’s going to end. Let your teams shoot with smaller cameras. Let them stay longer. Let the edit breathe. T he result won’t be polished but it will be unforgettable.

So what if it takes 18 months to make. Yes, it’s going to be hard but you know what? That’s where the gold is. That’s the gig.

So bring back observational documentary. People love it and it’s the one genre that, if we let it, can genuinely go toe to toe with YouTube. Not by copying it but by beating it at its own game: intimacy, unpredictability, and authenticity. After all, we invented that art form.

That’s how we win back audiences. That’s how we rebuild trust. That’s how we make documentary matter again.

This is why 24 Hours In Police Custody remains the best documentary series we have.

I watch a lot of real-life 'content' on Youtube. I was talking to someone the other day about how I get engrossed in these longer form videos. One of the channels I watch 'Kiun B' is a woman who lives in an artic town. It's just stuff about how people do things in extreme cold. Then there's people setting up stalls in Asia, or guys who go fishing/hiking/camping and there's one dude I watch who finds abandoned railway lines and travels them in home-built cars. For me, this stuff feels much closer to the old-school doc people like Hertzog used to make. The rawer, less glossy it is, the better. I want to see reality, not someone's 'artistic' version of it.