Has TV Become Too Regulated?

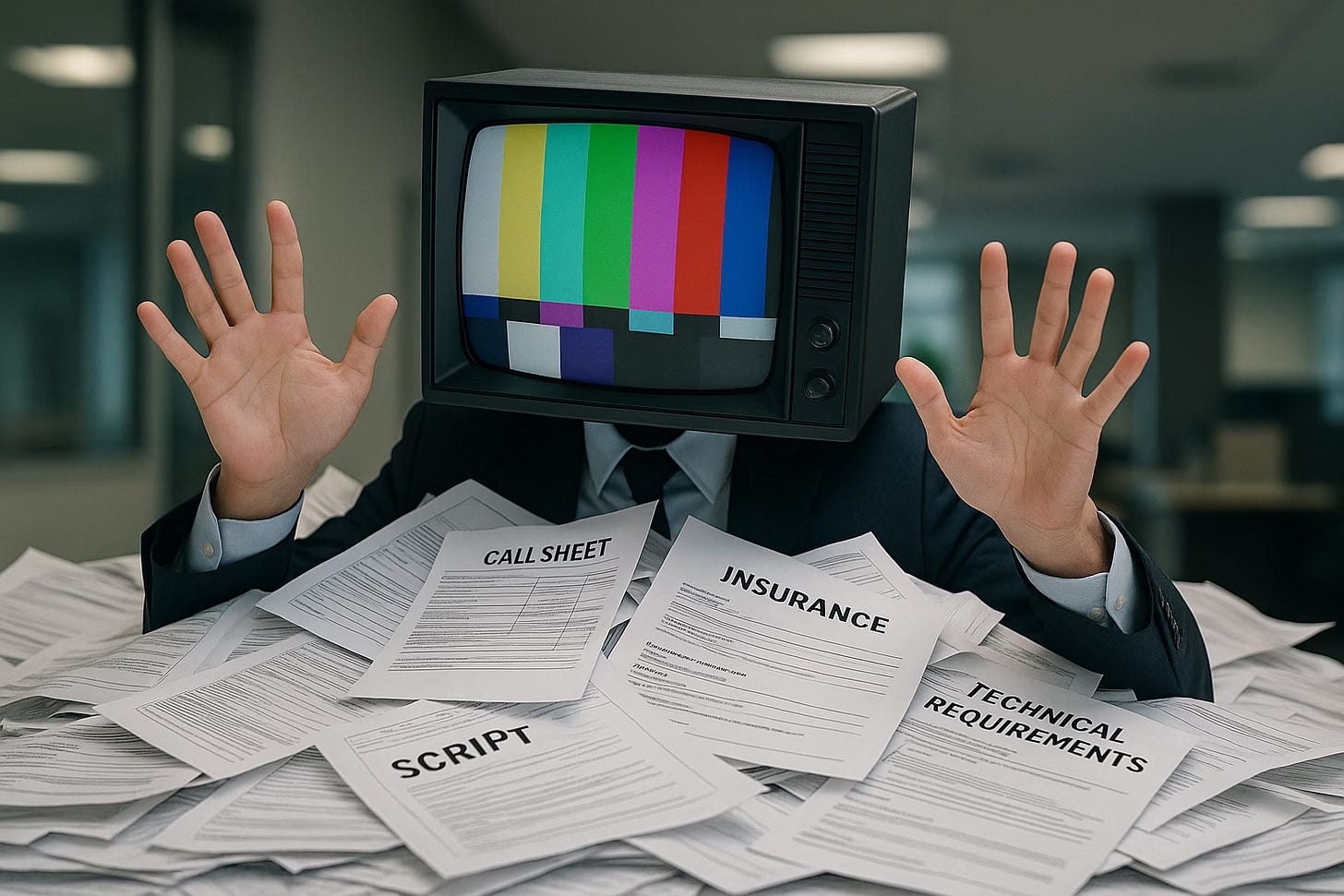

Last week I argued that YouTube’s lack of regulation is killing TV. But there is also a much more uncomfortable truth: television has become so risk averse, so over regulated, that we have strangled ourselves with compliance rituals and priced ourselves out of the fight.

I know to utter those words will sound like heresy to some. The instant assumption is that I must be arguing against workers’ rights, against diversity, or in favour of letting producers wave guns around on set without consequence. I am not. Nobody is suggesting we scrap the protections that matter. What I am saying is that over sixty years of regulatory layering has left us trapped in paperwork theatre, protecting what-ifs rather than people, and in the process, we have made TV uncompetitive in a digital age

.

From Wild West to nanny state

It was not always like this. In the 1980s, television was closer to YouTube than we care to remember. Crews shot wherever they fancied, release forms were virtually unknown, and if someone got hurt the company paid out and carried on. Risk was part of the job.

Remember when David Attenborough was famously bowled over by a silverback gorilla while filming Life on Earth? That raw jeopardy made extraordinary television. It would never happen now, a modern compliance team would shut it down at the first risk assessment, before a camera had even been switched on.

And consider the moral panics of the 1970s and 80s. When Johnny Rotten swore on live television with the Sex Pistols, it triggered national outrage, front page headlines and the suspension of presenter Bill Grundy. One punk singer’s profanity was enough to stoke a full blown moral panic.

Contrast that with today, when the horrific Charlie Kirk assassination video has been shared across digital platforms and not one government has called a public enquiry, or even said “enough is enough.” Back then, a single swear word provoked a storm. Today, violent content floods platforms without a raised eyebrow from those in power. And still, regulation piles higher on broadcast TV while digital remains largely untouched.

Paperwork theatre

Fast forward to now, and the rituals are everywhere.

The call sheet, once a vital tool, is now a novella: arrival times for every crew member, every phone number, screenshots of the nearest hospital. In practice, the PM and exec have the contacts on their phones, the runner has WhatsApp, and the location is a pinned drop. If someone is injured, we do not need a photocopied map, we need a car and Google Maps.

Or take safety. Of course nobody wants crew injured. But the way regulation has layered up, productions often end up preparing for risks so vanishingly small they border on the absurd. True story: I once had a production manager tell me I had to hire a Geiger counter to check whether the faint radiation from the illumination on an antique watch made it safe to handle. We had already consulted an expert, who said wearing gloves was sufficient. But because a box needed ticking, we wasted money proving something everyone already knew.

This is what happens when an industry becomes too risk averse. Instead of focusing on genuine hazards, we throw money at hypothetical ones. We mistake paperwork for protection, and in the process we lose sight of proportion.

Then there is E&O (errors and omissions) insurance. A commission already bakes in the cost of a broadcaster’s own blanket policy. Yet production companies are still forced to take out parallel cover. Two policies for the same show. It is the insurance equivalent of buying two umbrellas for one person and still getting wet.

And here is the kicker: most E&O policies come with an excess of around £10,000 that the production company has to cover before the insurance even activates. Which means many claims are simply cheaper to fix than to file. In practice, the broadcaster is covered, the producer is paying twice – I’d love to know how many times an E&O policy has been activated.

Or compliance. The production company spends time and money ensuring the cut meets the rules. Then the broadcaster’s compliance team does the same again. Duplicate notes, duplicate delays, duplicate costs. One standard, two owners.

And QC. Endless hours fixing GOP structures or gamma irregularities that no viewer will ever notice. YouTube ingests 4K uploads daily without demanding medieval pilgrimages through Baton reports. Broadcast could do the same, but will not.

These are not protections. They are rituals. They create the illusion of control while draining money from already fragile budgets. Here’s the mad thing though – it’s the channels themselves who are paying for all this. They say they can’t compete, yet they can’t wean themselves off covering themselves for infinitesimal risks.

Legacy deliverables nobody needs

Then there are the deliverables that have taken on a life of their own. Annotated scripts, for example. Nobody reads them except lawyers and archivists, and yet producers are still forced to spend hours delivering them. AI can and does generate them instantly – but have the channels asked anyone within their organisations whether they are actually used? If the broadcaster wants an as broadcast script, then let the broadcaster run the tool.

Production stills? Another box tick. We make producers grab photos on set, but if the channel needs reference images, AI can now pull clean stills straight from the final master.

Even the number of cuts. Rough Cut, Fine Cut, Programme Lock. Do we really need all three? Two would do the job. Every extra round means another week of edit time, more compliance notes, more cost, all for a marginal difference most viewers will never notice.

The important thing to remember: audiences do not watch the way they used to. They are often two screening, half scrolling Instagram or WhatsApp while your lovingly finessed archive shot plays in the background. I once asked a commissioner, who was asking for an extra archive clip, whether it would make the show £450 better. He admitted no. We / they did not buy it. Right call, nobody noticed.

This is not an argument for sloppiness. It is an argument for proportionality. For remembering that every deliverable is a cost, and that not every cost is worth it.

The political hangover

And here is the strangest part: politicians still act as if broadcast TV is the only medium that matters.

Look at the saga around Jimmy Kimmel. A single off colour joke on a late night talk show was enough to trigger a political firestorm and pressure networks into action. Broadcast comedy is still policed as if it can topple governments.

But does Trump, or any modern leader, really lose more sleep over a Kimmel gag than over the thousands of hours of unregulated, viral video attacking him daily on YouTube, TikTok or Rumble? That digital avalanche is far more vicious, far more dangerous to his presidency. Yet it carries almost none of the regulatory scrutiny broadcast still labours under.

Why? Because politicians are stuck in the old mindset that TV is “the” medium. And TV bosses, desperate to survive, keep reinforcing that myth. “We are still the most important platform,” they say, hoping for favours and protection. Meanwhile YouTube executives play the opposite game. They would never claim to be “the biggest show in town,” because the last thing they want is regulation. Better to stay quiet, re-enforce the lie that they are “just a platform,” and keep the freedoms that come with it.

So regulation piles higher on television, while digital sails by untouched. Which brings us to the kicker: in the unlikely event politicians finally grasp that it is regulation, not just audience drift, that makes TV so uncompetitive, what would deregulation actually look like? Which rules should stay and which should go?

Smart deregulation: protect people, not paper

If I were in charge of a channel here’s what I’d do. Let us start with what stays. Worker protections must remain sacrosanct: fair hours, prompt pay, anti bullying, safeguarding vulnerable contributors. Safety rules for genuinely risky shoots, stunts, extreme environments, minors, inclusivity and safety of contributors should never be watered down. And audience trust is non-negotiable: fairness in journalism, harm and offence standards, clear accountability when things go wrong.

But the rituals? They can go.

Call sheets should be shorter and live. One page with key times, location, hazards, and a link to a digital doc that updates in real time. Hospital maps? Everyone has Google Maps. Phone numbers? Keep them with the PM and exec, not blasted across a PDF.

E&O insurance? One policy per broadcaster, with productions named onto it. Cheaper at scale, cleaner in responsibility.

Compliance? One owner. Let the broadcaster’s compliance team be the arbiter. The prodco warrants good faith but does not duplicate the process.

QC? Move to a tolerance model. Hard fails for real issues like silent channels or severe sync drift. Soft fails for cosmetic quirks. The broadcaster decides whether to fix or ship.

Busywork? Annotated scripts, production stills, music cue sheets, automate them at the buyer’s end. AI can generate most of these in minutes. Producers should produce, not hand write archive fodder.

And instead of blanket bureaucracy, use randomised audits. Like food safety inspections, the possibility of spot checks keeps standards honest without forcing every project through the same grinder. Fail and you face stricter oversight next time. Pass consistently and you enjoy lighter touch.

This is not deregulation as chaos. It is deregulation as focus. Strip out the paperwork theatre, keep the protections that matter, and you buy back both money and creative oxygen.

The Result?

What happens if we do this? Budgets fall without cutting people. Insurance premiums drop. Producers spend more time producing, editors more time crafting stories. Broadcasters save, audiences get TV that takes risks again.

It is almost comic if you zoom out. In the 1960s, TV was the Wild West. By the 1990s, it was the nanny state. Now we live in a hybrid era: TV still trapped in over regulation, digital still running barefoot across the prairie. Politicians once terrified of television’s power have barely glanced at the platforms that now dominate elections, shape childhoods, and bend culture at scale.

Television, the medium that has lost dominance, is still treated as the dangerous one. Digital, the medium that has gained dominance, is still treated as a toy. No wonder the economics do not add up.

Are we the problem?

But here’s a thought: maybe the problem is not YouTube being under regulated. Maybe the problem is us. Maybe television has become addicted to its own paperwork? Is anyone in TVland bold enough to throw away the rule book and start again? Whoever does, will definitely win.

Deregulation does not mean throwing away protections. It means throwing away rituals. Call sheets that nobody reads. Duplicate E&O. Duplicate compliance. Too many reviews. Baton reports for phantom errors. Annotated scripts producers do not need. Filming in 4K when you only need to deliver in HD.

The danger is not recklessness. The danger is inertia. An industry so wrapped in its safety nets it cannot afford to leap.

If last week’s argument was “raise YouTube up,” this week’s is “take the weight off TV’s ankles.” Both can be true. We need a regulatory framework fit for a hybrid age, fast, fair, and focused on protecting people, not paper, otherwise we will have no industry left to protect at all.

This is fantastic.

Thanks Jonathan - and totally agree, although thankfully those breaches are few and far between. Aside from mind blowing breaches such as this - I do wonder how many times E&O policies have been called on - it would be great now. I would like to have more transparency around the subject...